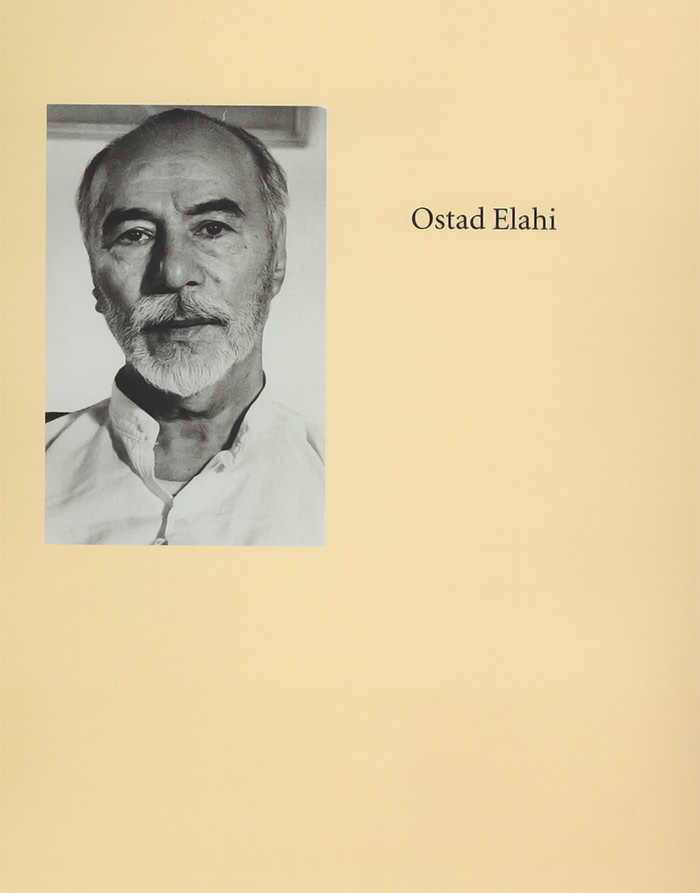

Map of Iran indicating the location of Tehran and Jeyhûnâbâd.

Road from Tehran leading to Western Iran indicating the location of Hashtgherd, Jeyhûnâbâd and Mount Bisotûn.

The Kurdish village of Jeyhûnâbâd, near the ancient town of Sahneh, is situated in a prosperous region of the province of Kermânshâh in the West of Iran. A dusty ten mile by-road connects Jeyhûnâbâd to the main provincial highway. Not far from this junction lies Mount Bisotûn, bearing on its stony flanks cuneiform inscriptions two thousand five hundred years old, attesting to the trials and triumphs of the great Aechemenian king, Darius I.

The village of Jeyhûnâbâd is, at the same time, a centre of the age-old Iranian mysticism, whose various denominations have greatly flourished in the Kurdish regions of Western Iran. Among the shrines belonging to the Saints responsible for shaping the distinctive spirituality of Jeyhûnâbad is that of the great charismatic mystic Hâj Ne’mat (1873-1921). He is the author of The Book of the Kings of Truth (Shâhnâmeh-ye Haqiqat), a hagiographic history in verse, reflecting the world vision of the mystic tradition of Western Iran. Henry Corbin1 once described it as “a Bible unto itself”.

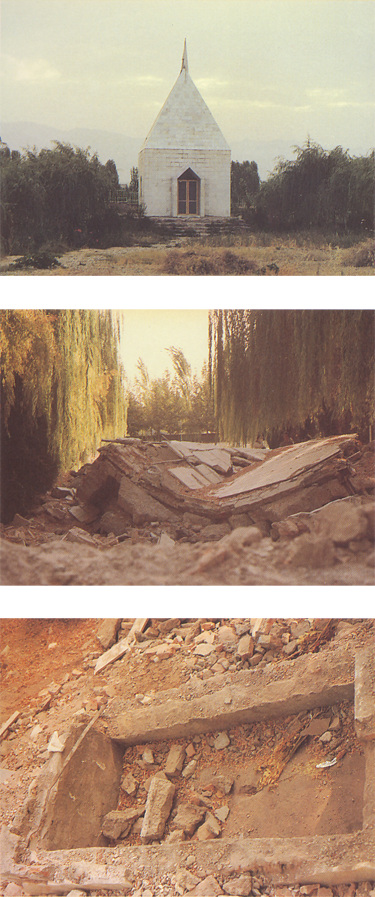

The shrine of Hâj Ne’mat in Jeyhûnâbâd continues to be a place of pilgrimage, frequented by the followers of the great spiritual tradition remoulded by Hâj Ne’mat, and taken to higher levels by his descendants. The cream-coloured concrete shrine with its pyramidal roof stands out in the heart of the village beside a complex of courtyards, surrounded by different rooms that include the family’s private oratory.

In one of these rooms, on the night of September 11, 1895, Hâj Ne’mat’s son was born. He was given the name of Fathollâh, nicknamed Kûchek’Ali (little ‘Ali). Since early childhood, his words and the sound of his voice had a powerful effect on human beings as well as animals. Aware of the uncommon intelligence and spiritual aptitude of his son, Hâj Ne’mat concentrated on developing Kûchek’Ali’s gifts from an early age and paid very special attention to his spiritual education and musical training.

1Henry Corbin (1903-1978), French scholar and authority on Islamic mysticism, who, as Director of the Institut d’Iranologie in Tehran, was responsible for the publication of the first edition of Shâhnâmeh-ye Haqiqat.

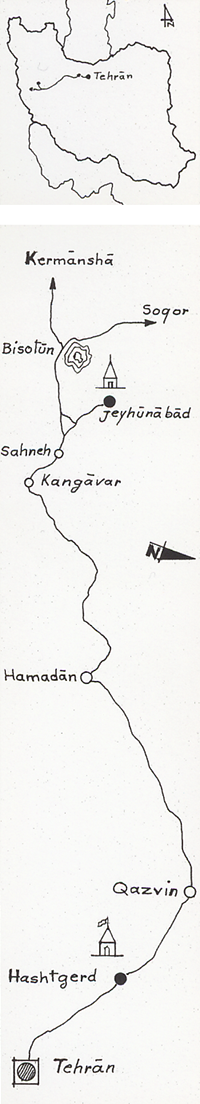

Jeyhûnâbâd.

Ostad Elahi’s room during childhood.

In those days, Hâj Ne’mat’s oratory was open not only to his immediate disciples, but also to ascetics and mystics who would come to Jeyhûnâbad from far-away places such as Mesopotamia, Caucasia, the Balkan Peninsula and India in order to benefit from his presence and join him in devotional and ascetic practice. Most of these travellers were adept at playing the traditional tanbûr2 ; and some of them were veritable masters of the modes and styles of their own regions. Their devotional chants and dances were nearly always accompanied by this ancient instrument. Young Kûchek’Ali spent a good deal of time in the company of those pilgrims. On his father’s request, each master taught him his own brand of traditional music.

At about the age of six, Kûchek’Ali was already acquainted with the technical intricacies of the Kurdish, Lorish, Turkish, Persian, Arabian and Indian styles of traditional sacred music. Love of music was an essential aspect of Kûchek’Ali’s spiritual aptitude, and the practice of it an integral part of his spiritual exercises. By the time he reached the age of nine no one could deny his perfect mastery of the sacred tanbûr. It was at this age that Kûchek’Ali took up the rigours of ascetic practice. Under the vigilant eyes of his father, his teen years were given to meditation, inner experiences and, of course, sacred music. Six decades later, as Ostad3 Elahi, he would sometimes provide his disciples with brief revelations about those early experiences:

We had a house that was convenient in every respect. It had a courtyard with rooms around it. […] That courtyard was called “the house of asceticism”. There, I had a room to myself. Sometimes, at night, I would take the tanbûr and engage in devotional music and chanting. Veils would then be lifted… I don’t know if they were fairies, angels or what. They would simply come and join me. I kept on playing. Often, my father would softly walk to the door, in order to listen. At times I would throw the tanbûr up into the air and then catch it. Even while it was in the air, the music did not stop and the instrument stayed in tune. Sometimes, I would find the room flooded with sunlight, and then I would notice that in the company of those angels I had been playing the tanbûr and chanting all night.4

Events of this nature constituted a constant pattern in Ostad Elahi’s life. The spiritual power which allowed such experiences to take place in these simple surroundings, also had an effect on everything he dealt with in his daily life:

2An ancient lute-like Persian instrument used solely in sacred music.

3Ostad is the Persian equivalent of Master.

4The italicised quotations in this biography are all from Asar ol-Haqq (Traces of Truth), except where otherwise indicated. This book contains the sayings of Ostad Elahi.

The mother of Ostad Elahi.

Malek Jân, the sister of Ostad Elahi.

I had once been given a partridge. This partridge fell in love with the sound of my tanbûr. Whenever I picked up the instrument, she would come and sit beside me, and after a while, she would become drunk with music and start making lovely sounds and scratching and pecking at my hand. […]At night, she would sleep in a niche in the wall. One early morning when I wanted to sleep, she decided that she wanted to sing. To make her stop singing, I shouted at her. She immediately became silent and, looking upset, she dropped her head. From then on, when she woke up early in the morning, she would walk to the foot of my bed, try to pull the cover off my feet and make a chirping sound. If I didn’t say anything, after a few tries, she would deduce that I was asleep and she would go away. Otherwise I would say, “How lovely.., what a wonderful voice ! ” She would then begin to sing.

The momentous event that transformed Kûchek’Ali’s essence, took place when he was no more than eleven years old. At that time he was accompanying his father on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Soltân Es’hâq5 in Kurdistan’s mountainous region of Owrâmânât. A mysterious illness struck him, and three days later, in the evening, he died. The custom in Iran being that the burial take place on the day after the death, while a grave was being prepared, someone was dispatched to a neighbouring village to buy a shroud. At sunrise, before the man set out to perform his task, a messenger sent by a well-known mystic seer 6 came to inform him that Kûchek’Ali was not dead, but reborn. The seer had also sent a note for Hâj Ne’mat: “O joy! Nour’Ali 7, blessed be his arrival! The one my father and I have awaited for so long, is now yours.”

And it was then that the name of Kûchek’Ali was changed to Nour’Ali , for, as he himself has said, “another soul was breathed into my body”.

Nour’Ali’s next ten years of devotion, asceticism and learning were spent beside his father, and when he reached the age of twenty, he was a perfect sage, a thinker in the true sense of the word, a great spiritual master and a peerless musician. The exceptional convergence of Nour’Ali’s gifts was clearly more than the simple blossoming of precocious talents of a gifted child, especially since, until that day, the young Nour’Ali had had no contact with the outside material world other than through books and lessons. His father had repeatedly referred to this fact in these words:

[…] It is as if I have raised you in a fine garden. If you look beyond the garden walls, you’ll see nothing but dirt and garbage.

In the last years of his life, Ostad Elahi would recall those days with a certain tenderness:

5Great 13h century mystic, founder of the order of the Ahl-e Haqq (Companions of the Truth).

6Sheykh Hesâmoddin, leader of the mystic order of Qâderis -a seer known for his charismatic powers.

7Nour’A1i meaning light of Ali. Nour= light. Ali = one of the names of God, meaning sublime.

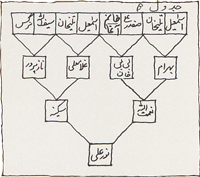

Family tree designed by Ostad Elahi.

My life had all been spent within the same four walls, and nothing but words of truth had reached my ears. I didn’t have any contact with society. I couldn’t imagine that someone could lie or cheat. I took it for granted that every place was like our own house.

This saintly detachment had led the young Nour’Ali to contemplate the possibility of celibacy. But, in compliance with his father’s wishes he married and his first child was born in that same “fine garden”

His systematic ascetic discipline and his ceaseless practice of what he was learning produced a vision that eventually gave a new meaning to the concept of “truth”, ultimately leading to new discoveries on the path of man’s progress towards Perfection. It became clear that spirituality is a precise science that cannot be truly attained without practice. Mere knowledge of its theories will lead nowhere and full understanding of it is possible only when the spiritual traveller succeeds in assimilating all its elements through personal experience. In time, the master innovator of spirituality made clear the distinction between what is truly the “Truth” and what is being bandied about in the name of truth by some established old spiritual patriarchs.

The revolution in the method of seeking truth coincided with important historical upheavals and the beginning of changes in social relations. As the world was preparing to face the challenge of the twentieth century, new flowers were blooming in the spiritual world and a new fragrance was about to permeate the souls that longed for it. For the longing soul also knew that the old chapter of spirituality, drawing mainly on ecstasy and confined to secluded meditation, was about to end and give way to a new cycle of responsible thinking, analysis and social commitment. The quest for perfection was no longer to be pursued in the tranquillity of ascetic seclusion, but in the thick of constant clash between temporal attractions and spiritual longings, the soul thus coming to grips with the fundamentals of Divine Intent.

Even a great mystic such as Hâj Ne’mat, whom Gurjieff calls the “Saint of Jeyhûnâbâd,” found himself unprepared for such change:

The situation will change so totally that I will not be able to face it. I have asked God to let me go sooner.

The young Nour’Ali, who was to become, by God’s will, the future master of the new order, found himself abandoned even by the disciples and devotees of his father, once Hâj Ne’mat passed away. His followers, imagining that the “hearth that once was, was now extinct”, all scattered and Nour’Ali was left without a friend. Even the servant in

8Gurdjieff the mystic author of Meetings with Remarkable Men, who had met Hâj Nemat in the course of his extensive travels in the Middle East and Central Asia.

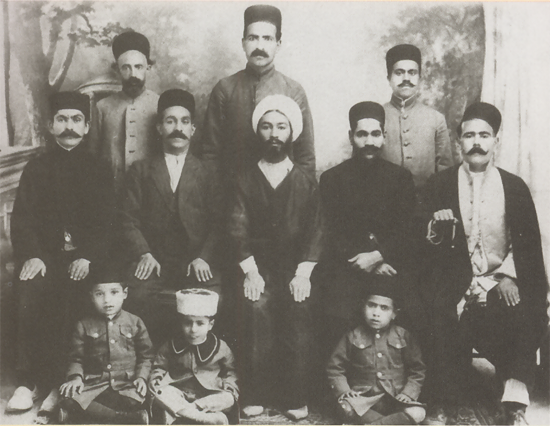

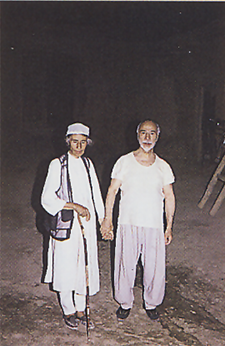

At the age of twenty-six, among his followers.

charge of milking the cow dropped the bucket and went away. Old friends became new enemies and some of them even threatened him with death. Except for his devoted mother, wife and loving sisters, Nour’Ali seemed to be totally alone in this world. But his serene detachment in a “sea of troubles” seemed to suggest that he considered the whole predicament as a minor prologue to the great changes he was ordained to bring about. That was probably why it did not take his “new enemies” more than a year to turn into faithful disciples, and for large numbers of outsiders, Jeyhûnâbâd became a focal point of pilgrimage.

For Nour’Ali, no event was an accident, and nothing could ever occur outside the sphere of God’s will. It was within that “sphere” that about a decade later, the time came when he had to step out of his father’s “fine garden” and prepare to test his discoveries in the crucible of society at large. In time he came up with precise models that served as simple guidelines for those who would travel the Path of Perfection as charted by Ostad Elahi in the course of a lifetime of careful deliberation. That was when he would say to his dedicated students:

You should not withdraw from society, take to ascetic seclusion and pray like old mystics. You must remain in society and

Part of the house of the parents of Ostad Elahi.

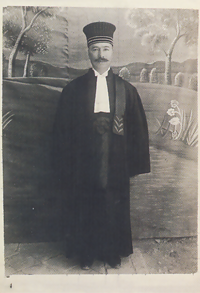

In judicial robes.

keep your attention focused on God at the same time. For instance, when you go to the cinema, it should be as if you have gone to a place of worship.

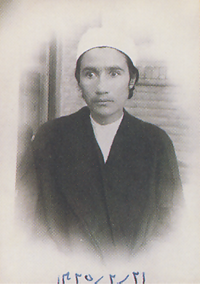

In step with the rapid changes that swept through many societies in the early twentieth century, young Nour’Ali cut his hair and beard — his mother treasuring the cuttings in the family chest — and, dressed in modern clothes, took a job at the Registry Office. He did this to mollify a suspicious government which had been misinformed about the “ultimate designs” of a man who had the power of moving the hearts of his fellowmen. Later, resolute as ever, Nour’Ali went to Tehran and took a lodging in the old district of Sangelaj. There he succeeded in passing the three-year course of the Superior School of Jurisprudence within six months. Disregarding his own personal preferences, he then entered the Ministry of Justice at the age of thirty-six — an eloquent example of submitting to God’s will and fulfilling his duties towards both himself and his fellowmen. There he began a long judicial career that took him to many parts of the country. As an impeccable judge and a perfect prosecutor, he was destined to make brilliant use of his tutored talents throughout the next decades:

God made me take up a public career despite my aversion to it. He forced me to become a judge and gave me sensitive judicial assignments, each of which I realised later contained a thousand pearls of wisdom. Before taking up government employment, I was unaware that my twelve years of devotional and ascetic practice had no more value than one year of public service. Official duties and sensitive assignments, rife with all manner of things which I would not have any dealings with, […] each of the latter years were as rewarding as the whole of the former twelve put together. That is why I say, be in society, keep your belly full, strengthen your constitution, but make sure that your soul is so fortified that it can resist any temptation.

The official files at the Ministry of Justice bear witness to Nour’Ali’s far-sighted approach to seemingly insoluble problems, his uncompromising firmness in the face of injustice, his noble discretion in dealing with vulnerable witnesses and in the end, his balanced assessments, his carefully calibrated pronouncements and adamantly judicious verdicts, even when subjected to strong pressures. He was always a paragon of fairness in the eyes of his higher and lower associates, who often knew nothing about his exceptional essence. They were all astonished to have a judge before their eyes, who had no interest in rank and power, yet was most serious about any position he happened to hold; a public servant who had an unconventional attitude towards

Among colleagues.

everything, yet was always punctual and careful about his duties; a man who was fully immune from material attachments, yet most precise in dealing with everything that was material; one who, for instance, wouldn’t even use an office pen for writing a personal letter; one who would voluntarily work overtime at home, or in the office, to finish the remaining files, until dusk, when his office manager would step into the office, cough discreetly and mumble:

“It’s seven o’clock sir:’ and then put on the light.

In the course of his near thirty-year career, Judge Nour’Ali Elahi proved the guilt of many murderers, but never passed a single death sentence.

He gave equal attention to the needs of people from all walks of life irrespective of their social status. This attitude was not a matter of mere discharge of official duty. It stemmed from Nour’Ali’s profound conviction that “God’s satisfaction” is the ultimate criterion for evaluating human action. He used to say:

A judge who looks to God for guidance, is invariably helped by Him and shown the right path in critical moments of judgement.

That is why, when he reached a definite conclusion about a case after sufficient deliberation, no recommendation from any authority could affect his decision, and no threat from any source could shake his heart:

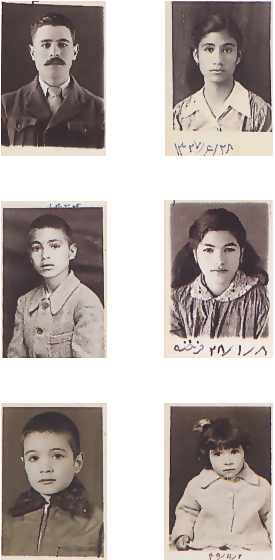

His six children.

As a judge, I would do things that no one dared to do. That was because I was accountable only to God and not to the Ministry, and I wasn’t afraid of anyone.

His patience was particularly inexhaustible when trying to establish the rights of the defenceless. The swindler who, through bribery, had taken repossession of an orphan’s entire fortune would, in time, be forced to hand back everything he had laid his hands on. And when, emboldened by the protection he had received, the victim eventually tried his hand at wrong doing, he too was justly put in his place.

Even a murdered woman who, in a dream, pleaded with him for justice, benefited from his thorough attention. Her closed file was unearthed, and the facts leading to the conclusion that she had died a “natural death” were painstakingly separated from evidence contaminated by bribery. His insistence on exhuming the body in the face of strong opposition on the part of her relatives, ultimately made it possible to prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that she had been murdered by those same relatives, who had conspired to divide her fortune between themselves. Neither his colleagues nor her relatives could understand the “method” that made it possible to render justice in this way.

In the lexicon of Ostad Elahi, the question of “rights” is not confined to technical arguments about the murderer and the victim, the plaintiff and the defendant, the innocent and the guilty. From his point of view the whole universe is a court of Divine Justice. Every visible as well as imaginable object is endowed with special rights of its own. To infringe upon any of those rights produces a reaction proportionate to the infringment which must inevitably lead to the redressing of the offence and the restoring of the balance, according to the Divine Law of Justice. No creature, be it living or inanimate, and no object, visible or invisible, is exempt from this law. To recognise the “rights of objects”, each in its own place, and to respect them at all times, is one of the essential duties of those who “walk the path of God”.

The account of the student who hung Ostad Elahi’s overcoat, hat and scarf on one single peg provides us with an illustration of respecting the rights of objects as well as a clear example of Ostad Elahi’s daily conduct:

One winter day I was at his house, waiting for his return from one of his daily walks. He opened the door of the hallway at the precise moment he was expected to do so. I took his overcoat, his hat and his scarf and, as he went out of the hallway, I hung the three of them on one of the pegs of the hatstand beside the door. A while later, returning to the hallway, he fixed his eyes on the hatstand, saying: “Why have you hung the three of them on one peg?” Then, taking his hat and scarf off that peg and hanging each of them on a different peg, he continued, “You shouldn’t overburden any of these, each of them has a duty of its own.” 9…

9These episodes are recounted by a student.

If the rights of inanimate objects carry such weight, what of the rights of people and, ultimately, those of God?

When the rights of all objects are respected, balance ensues. This judicious weighing was a routine practice in Ostad Elahi’s daily life:

One day, he wanted to help shift a bed from one place to another. He got hold of the bed’s corner with his right hand, but didn’t lift it. “No,” he said, withdrawing the hand, “The right hand has been given enough work since this morning, it’s now the left hand’s turn.” Then with his left hand, he helped shift the bed

According to Ostad Elahi, equilibrium is a pivotal factor in everything. Any deviation from this principle creates a reaction:

Equilibrium, meaning that “the best position is the middle position,” should always be borne in mind. The “straight path” also means that the “best position is the middle position.” The straight path is the one that eliminates both extremes from life in this world and the next. The word straight contains the idea of right, which is the opposite of wrong. When something is straight, it’s right; and when it’s right, it’s true.

God’s justice and the order of the universe are dependent on one another. This “interdependence” is not specific to only higher matters of creation, but also applies to all the minutiae of daily life. To be aware of this and not to lose sight of its meaning, even while attending to simple routines, is to be in harmony with the “order of the universe”:

It is mostly through the ordinary matters of life that I have come to realise the significance of the order of the universe. The order bestowed on the universe by God, testifies to His justice. Justice is the requisite for all order. Order affects both life and afterlife. It must apply to everything and it should begin with little things. One should, for instance, put an object in a place where one can find it even in the dark […]. Once a person gets used to orderliness in material things, he will certainly be orderly in spiritual matters too.

Once the correlation between equilibrium10, justice and order on every level is properly understood, the significance of Ostad Elahi’s insistence on the “rights of everything” becomes clear. It is then possible to know the reason for his equal treatment of all that there is, from the highest to the lowest. The logical

10It is interesting to note that the word ‘adl’ (justice) is the root from which ta’âdol (equilibrium), is derived.

Among friends.

conclusion to be drawn from contemplating such a vision is that only awareness of everything at all times, is likely to lead to it; nothing short of total compassion towards all creatures can insure the full application of that vision in the practice of daily life. Only a perfect soul would be capable of such perfect harmony, setting an example for the spiritual traveller on the “straight path”, who seeks Perfection in its full sense.

As Ostad Elahi’s new approach to the concept of “man’s progress towards Perfection” was gradually being expanded by him for those who sought his guidance, he began to address the age-old problems of several million adherents of the Ahl-e Haqq order11. Centuries of ignorant deviation from their spiritual roots, had resulted in a fractured tradition, causing different Ahl-e Haqq clans to go their separate ways.

With his hallmark of patient diligence, Ostad Elahi unearthed the forgotten tradition of the early Ahl-e Haqq order, collecting a great number of sayings and sacred chants of saints and seers and resurrecting many forgotten documents. Sifting through the findings, he separated the wheat from the chaff, setting aside the retrieved material that was to form the factual basis for his later work.

The opportunity for continuous authorship presented itself in 1957, when his retirement ended his judicial career. Free at last to use his time as he wished, he settled in Tehran and began to work regularly on his collected documents in conjunction with a more systematic concentration on his music.

His first book, Borhân ol-Haqq12, published in 1962, presents for the first time an authoritative view of the historic and spiritual background of the order of Ahl-e Haqq, also providing full accounts of its development and its sacred rites. A sizeable chapter, containing many important questions asked by attentive students and answers given by Ostad Elahi, was later added to the book. This version, as the sole reliable source of information on the history and rites of the Ahl-e Haqq, has been reprinted many times in the last two decades.

The second work by Ostad Elahi, Ma ‘refat ol-Ruh13 deals in detail with the question of the soul, the proof of its existence and immortality, and the various stages of its progress towards its final destination.

Sometime after the publication of the first edition of Borhân ol-Haqq, the open house kept by Ostad Elahi to a circle of his friends and new students became a regular event on Monday nights. People in need of guidance, came to those gatherings from Tehran, Kermânshâh, Shirâz, Paris, London and other places, seeking and finding solutions to myriads of questions.

11A mystic order founded in the 14th century in Western Iran. Ahl-e Haqq literally means “Companions of Truth”.

12Proof of The Truth.

13Inner Knowledge of the Soul.

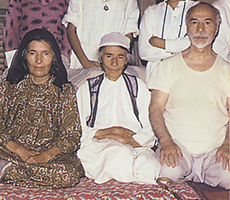

Ostad Elahi holding his youngest son.

With a smile that conveyed boundless compassion and authority at the same time, Ostad Elahi had a kind word for everyone. He would inquire about their health, their family, the accident that had occurred or was about to take place, the dreams they had had the night before, the thoughts crossing their minds and the questions not yet asked, but seemingly known to him already. He would say, for instance, “Whatever made you think such a thing my dear?” or “You speak as if you didn’t have a father, my child.” His words flowed with breathtaking simplicity, and affected you in all kinds of unexpected ways. “Is this some grace?“ you were likely to ask yourself, “Or just a routine spiritual experience? Or simply an expression of kindly attention from a perfect being?”

The states of spiritual euphoria — or ecstasy, if you like — reached through sacred music and prayer in those gatherings, were not an end in themselves, but a means to help prepare the soul for the assimilation of the hard lessons it had to learn, if it were to make any headway on its return to its origin.

Ostad Elahi’s “simple words” about the complex spiritual mysteries and strange happenings in faraway planets, made those mysteries and happenings appear as familiar as ordinary matters of daily life. And yet, every word, no matter how simple, and every allusion, no matter how delicate, was a lesson to be put into practice, or a metaphor for some urgent reality, to be borne in mind. They felt, at times like caresses, at times like dark forebodings. Sometimes they were a cure for an ailing soul, sometimes medication for a sick body. People were treated according to their needs. A student recounts:

Once, two young men from Europe showed great enthusiasm for Ostad Elahi’s teachings. Out of respect for his words, they had refrained from drinking alcohol for sometime; but they missed it, nevertheless. One day, one of them said to him: “It’s true that you discourage people from drinking, but I like beer. What am I to do?“ Laughingly, the Master said: “But as a Christian, you are free to drink. There is nothing to stop you.” Next week, the other young man said: “I had some beer the other day, and it gave me a stomach-ache.” “Why did you drink?” Ostad Elahi asked, with a serious expression. The young man was surprised. “Didn’t you say that a Christian could drink?” he asked. Ostad Elahi said: “To your friend, yes, but not to you. You shouldn’t drink!”

Reproaches for your faults, even when sternly delivered, were at least as much imbued with gentle kindness, as accolades generously bestowed for your merits. There were occasions when an awesome outpouring of displeasure was eventually followed by the purging fire of his music that had the power of melting any heart into liquid gold.

Ostad with the elder of his sisters, Malek Jan.

Now, twenty one years after the departure of Ostad Elahi from this world14, what went on in the course of a decade, on those Monday nights, might have simply seemed like an enchanted dream, were it not that some farsighted students took to putting down, word for word, everything that was uttered by him. Indeed, even then, faulty interpretation of what was happening had led, in many instances to the “dreamy” notion that attending those gatherings was merely to bring peace, euphoria, and contentment to participants, charging their spiritual batteries, as it were, enabling each of them, eventually, even to develop spiritual powers.

The awakening was abrupt and painful. Monday-night gatherings were suddenly cancelled, and everyone was stunned, not knowing what had happened. No amount of pleading by distraught students seemed to make any headway; until, finally, the occasion of a religious feast provided the opportunity for everyone to extend their greetings to Ostad at his house. Ostad Elahi used that occasion to tell his immature students what they were in need of knowing:

I came to your gathering to tell you about something I wanted you to do. In fact, a new page was to be turned for you. But Ifound you in such a bad state that I left the place in anger and disgust. I didn’t expect that at all. You were completely disunited. Then, two nights ago, I saw you all in a dream, standing near my room, looking at me with anxious questioning expressions on your faces. Friends came and insisted we make up, though I didn’t want to. […]

There may be more than a million people who count themselves as my friends, and the reason for their friendship is that they each expect something from me. Some want to have children, others want their children not to die, still others have job problems. In brief they are all my friends because they expect me to do something for them. I treat them as they wish, and we don’t expect anything else from each other. They come from far-away places, to ask for a tabarok15, and I gladly give it to them. […]

But among my friends, there are afew who want to enter the school that I, myself have entered. This small group is in a different category altogether. We treat each other in quite a different way. They want to “attain Spiritual Perfection”. “Spiritual perfection” is easier said than attained. Even in the books of the prophets and biographies of the saints, you only come across a limited number of their followers who are quoted as having uttered those words. The rest have aimed at nothing higher than striving for righteousness, distinguishing between the religiously licit and illicit, and leading an honest life, by trying their best to do the biddings of prophets and saints.

14“Unicity” was published in 1995.

15Blessed object given by a holy person.

With his two sisters.

A photograph taken in his later years.

Striving for Perfection is another matter. On the Path of Perfection, when Nassimi16 is skinned alive, his Master says “it was his duty, nothing more.” To contemplate the process of Perfection, takes courage which everyone doesn’t have. You can put this phrase out of your mind and stay friends with me. We can go on as father and child. You can come; we’ll talk. I’ll give you some tabarok too, if you like, but I won’t have anything to do with your spiritual progress. With you, I’ll be just as I am with others. You will go on living your lives, and be happy or even righteous if you wish. But when you are talking about the “attainment of Perfection” you are dealing with an entirely different matter, a different undertaking altogether. Our relationship would be different then, so would our expectations from each other. The least thing you do would be taken into account.[.. .]You must be very careful, and you should be aware that, as a result of your presence in this school, your smallest actions are revealed to me. If I make no mention of them, it’s because it is beneath both you and I for me to keep on questioning you about them. On the other hand, if you look carefully, you’ll find that there is nothing l haven’t somehow reminded you of.

Now, if you intend to come here together, with the intention of struggling for the attainment of Perfection, you must abide by three conditions. First, you must be truly like brothers and sisters, […] as befits my spiritual children. Second, you must completely separate the material life from the spiritual life. Your worldly routine mustn’t interfere with your spiritual obligations. You must refrain, absolutely, from interfering with each other’s material affairs, and keep your relations strictly on the spiritual level. Third, let your tongue speak truly what you feel in your hearts. Do not speak badly of anyone behind their back and flatter them when they are present. Try, all of you, to be united and of one heart!…] You are like the beads of a rosary, held together by a string. If the string snaps, you will all be scattered, even if some of you are not at fault. In your circle, one or two were guiltless, but it was no use. When the string snaps and the circle is broken, the guiltless too will burn in the fire raised by the others […].

Thus, Ostad Elahi’s Spiritual University took shape on Monday nights and his teachings — later expounded in The Path of Perfection17 by his son, Dr. Bahram Elahi — was redefined in a formal manner. From then on, there were conditions to attending Monday night classes. Regular attendance became a much more serious concern for everyone, and questions and answers, a much more precise practice.

16A 13th century martyred saint.

17The original French version of this book, La Voie de ía Perfection, has been translated into six languages thus far.

The shrine after being torn down.

In later years, on most evenings, Ostad Elahi allowed a number of students to benefit from his presence. The lessons he gave in those unforgettable gatherings had an exceptionally uplifting effect on everyone, and the poignancy of his presence in the last few months of his life is beyond description.

The notes the far-sighted students took in the course of all those years have been compiled under the title Asâr ol-Haqq18, two volumes of which have already been published. The spirit of the teachings of Ostad Elahi are well captured in these volumes.

After the passing of Ostad Elahi on October 19, 1974, at 11 am, his sister, Sheykh Jâni, who was also his “perfect pupil”, had the mission of transmitting his teachings.

Ostad Elahi left a widow, three sons and three daughters.

On the day of his burial near the rural town of Hashtgerd, seventy kilometres to the West of Tehran, a stunned multitude gathered around his half-constructed shrine to pay him their last homage. There were many who were overwhelmed by the gentle serenity of his face before burial.

Ostad Elahi had always said that the physical body of a saint of the highest order does not remain in this world after death. Some eight years after his death, misguided souls, bent on discrediting his teachings, decided to tear down his shrine and desecrate his body. The task that proved impossible by picks and shovels, was finally achieved with a massive bulldozer. When the tomb finally lay open before their eyes, they found it empty.

Two more years passed before the shrine was reconstructed in its present form. It continues to be a place of pilgrimage, not only for those who had the grace of knowing him personally, but for thousands of students from many parts of the world who have entered the Path of Perfection since his departure from this world.

18Traces of the Truth.